Ich bin ein Berliner

20 years ago today, on November 9th, 1989, the Berlin Wall fell, and history changed again.

If one were to select one city to exemplify the struggles of the 20th Century, Berlin would certainly be a prime candidate.

Germany’s aggressive turn-of-the-century empire was ruled from Berlin, leading to the devastating losses of WWI and, some scant 15 years later, the ascendancy of Hitler’s National Socialism (Nazi) Party starting in 1933. In 1936 Berlin hosted the Olympics and of course was the seat of German power for WWII from 1939 to Germany’s loss in 1945.

But to describe Berlin’s story from that point simply as a “loss” is to radically downplay the city’s experience.

Starting from the Allied raids in 1943 (involving sometimes up to 1,000+ bombers per night) to the shelling of the city in the final Battle of Berlin, more than half of downtown Berlin was completely laid to waste, a destruction whose human casualties were vastly amplified by Hitler’s refusal to allow any evacuation of German civilians.

As the war drew to a close, it is Stalin’s Red Army, and not the Allies, that rolled in from the east to defeat the last of Germany’s army in Berlin. In the final days, Hitler committed suicide in the bunker underneath Berlin’s Reich Chancellery on April 30th, 1945, and two days later on May 2nd Berlin’s Germans capitulated to the Red Army.

The Soviets were not gentle invaders. Apart from the brutal and often indiscriminate murder of civilians and refugees, it is estimated that between 130,000 – 1,000,000 German women and girls were raped, some as young as 8 years old (with suicides among the traumatized victims running as high as 10%). This did not stop until two and a half years later, when Soviet troops were confined to carefully guarded camps.

In addition, when the Allies arrived in Berlin a month after its fall, they found a completely inoperative infrastructure (no garbage disposal, sewage, etc.), and the average Berliner barely subsisting above starvation at some 800 calories a day.

(I describe these things not to downplay Germany’s ultimate responsibility for the war nor their own atrocities in its conduct, but simply as an honest representation of the historical events that Berliners lived through.)

Although Berlin was deep inside the German territory that the Big Three (Britain, U.S., Soviet Union) had agreed would be administered by the Soviets after the war, Berlin as the capital was also divided among the Allies. Thus, the half of Berlin that was Allied-controlled (later known as West Berlin) lay in the heart of Soviet-controlled Germany, one street over from Soviet-controlled Berlin (East Berlin). This led to two very important post-war developments.

In 1948, the Soviets blocked all overland routes from West Germany across its territory to the Allied-administered West Berlin, with the intent to apply enough social and political pressure to force the Allies to cede their part of the city. Instead, the United States and Britain over the course of a year flew over 200,000 cargo flights supplying some 13,000 tons of food a day (plus petrol and other supplies) into West Berlin. At its height, what became known as the Berlin Airlift saw a cargo plane land in West Berlin every 30 seconds. Outmaneuvered, the Soviets reopened Allied rail access to Berlin some 15 months later.

What Berlin became famous for, however, is the Wall.

Run by the Socialist Unity Party under the watchful eye of the Soviets, East Germany was not nearly as pleasant and prosperous a place to work and live in than its capitalistic counterpart in the West. Although all borders between East Germany and West Germany had been closed (to East Germans) for some time, those who wished to emigrate could easily do so by traveling to East Berlin, walking across to West Berlin, then taking a flight out to West Germany. It is estimated that prior to 1961, some 3.5 million East Germans emigrated to West Germany, especially the young and well educated.

Soviet leader Nikita Krushchev proposed a simple solution: build a wall. At midnight on August 13th, 1961, East German troops closed all crossings from East Berlin to West Berlin, tore up streets, closed metro stations, and installed barbed wire and fencing around all 124 miles of West Berlin, including the 27 miles directly through the middle of the city. From there, the barriers were over time further refined and improved with watchtowers, multiple layers of wire and walls, patrols and dogs, trenches and beds of nails. East German soldiers were ordered to shoot any East Germans trying to cross into West Berlin (whereas West Berliners could freely travel to East Berlin and back).

The wall stopped the East German emigration problem cold, from 3.5 million in the years prior to just a few thousand successful escapes in the decades following (and several hundred killed in failed escape attempts).

Although the erection of the Wall was a clear Soviet violation of the agreements between the occupying forces, President Kennedy’s administration, right on the heels of the Bay of Pigs fiasco, saw the new Wall as a convenient means to defuse Cold War tensions (as Kennedy is quoted as stating to his aides “a wall is a hell of a lot better than a war”). After some token official protests, the United States informed the Soviets that they accepted the new Berlin Wall as a “fact of international life.” Nevertheless, Kennedy’s administration used the wall to highlight the inadequacies of communist rule worldwide, and a couple of years later in 1963, he made one of his most famous speeches in West Berlin that referenced it (the eloquent “Ich bin ein Berliner” speech, well worth reading in its entirety).

The years under the Socialist Unity Party rule were not easy ones for East Germans: the State collected 97% of incomes (to redistribute), standards of living were far below their Western neighbors, shortages of even basic food staples were common, and the waiting list for a new car was 13 years. On top of economic misery, East Germany’s secret police, the Stasi, were ruthlessly efficient and repressive, with one operative for ever 67 citizens and a significant portion of the population under surveillance or being informed upon (a far more pervasive penetration than the previous Gestapo or even the Russian KGB).

Twenty four years after Kennedy, it would be another great speech that would elevate the Berlin Wall, now the most prominent symbol of the Cold War, to the headlines: Ronald Reagan’s address in front of Berlin’s Brandenburg Gate in June of 1987:

“We welcome change and openness; for we believe that freedom and security go together, that the advance of human liberty can only strengthen the cause of world peace. There is one sign the Soviets can make that would be unmistakable, that would advance dramatically the cause of freedom and peace. General Secretary Gorbachev, if you seek peace, if you seek prosperity for the Soviet Union and eastern Europe, if you seek liberalization, come here to this gate. Mr. Gorbachev, open this gate. Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall!”

Interestingly, both the State Department and the National Security Council had strongly objected to this section of the speech, but Reagan insisted on keeping it. “It’s the right thing to do,” he told his deputy chief of staff in the car on the way to the Wall. The Soviets were not impressed and their press in response called Reagan a warmonger.

In 1989, eastern European dominoes began to fall. Poland became the first eastern bloc country to hold elections in which an anti-communistic party took power, and both Hungary and Czechoslovakia began to liberalize their trade and emigration policies with the West. As soon as Hungary demilitarized its border with Austria, some 13,000 East Germans vacationing in Hungary attempted to defect, and similar developments took place in Czechoslovakia. Meanwhile, millions of East Germans protested in Berlin for greater freedom.

In response, the East German government decided on November 9th to announce a gradual, moderate liberalization of its borders with West Germany. However, the East German politburo spokesman that was handed this announcement was not fully briefed that this was to be a gradual new policy, to start at some time in the future. He read the announcement and when pressed by reporters on timing, replied: “as far as I know effective immediately, without delay.”

This news was picked up by West German TV stations, who announced that “starting immediately, [East Germany’s] borders are open to everyone.” East Germans listening in flocked to the Wall and demanded that the guards let them through. Frantic telephone calls from the stunned guards to their superiors followed, with no one along the chain of command willing to take responsibility for authorizing the use of lethal force to stop the wave of people. And so, on November 9th, the overwhelmed guards stood aside as thousands crossed and climbed the walls, reunited with their West German neighbors for the first time in 28 years.

Almost a year later, on October 3rd, 1990, East and West Germany were officially reunited as one country after being separate since 1945, and in 1999 Berlin became once again the capital city of a united Germany (Berlin was always the capital of East Germany, but West Germany’s capital during the years apart was Bonn).

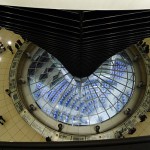

And today? Once the symbol of Cold War division and tension, the Berlin of today is a forward-looking, vibrant city teeming with culture, festivals, tourism and infamous nightlife. From a city difficult to get to for Westerners or quasi-impossible to get out of for Easterners, it’s now a bustling international metropolis that attracts some 8 million visitors annually.

Most of the Wall (except for a few small sections kept for historical purposes) has been torn down, but its location is everywhere marked by cobblestones indicating where it once stood. Look for the picture below with the BMW parked “on top” of where the Wall once stood, a fitting image to replace Berlin’s 20th Century status as one of the world’s most troubled cities to one of a new 21st Century era of German openness and unity.

In the words of John F. Kennedy:

“Freedom is indivisible, and when one man is enslaved, all are not free. When all are free, then we can look forward to that day when this city will be joined as one and this country and this great Continent of Europe in a peaceful and hopeful globe. When that day finally comes, as it will, the people of West Berlin can take sober satisfaction in the fact that they were in the front lines for almost two decades. All free men, wherever they may live, are citizens of Berlin, and, therefore, as a free man, I take pride in the words ‘Ich bin ein Berliner.'”

Click to subscribe via RSS feed

Click to subscribe via RSS feed

What is that in 51 a memorial of some sort?

Yes, it’s Berlin’s (highly controversial) Jewish Holocaust Memorial.

‘Krasivaya’, Gabriel!! And great post!! VERY befitting to a 20 year anniversary. . .

Spasiba, Sarah!

Wonderful! My favorite picture is the BMW crossing the wall.

Thanks Maryam!